From Tobacco Fields to Data Centers

Rocky Mount's Economic Evolution and Lessons for the Future

Working in Washington, D.C., it’s easy to see the world as a series of high-stakes political dramas. That perspective has its uses, but it can also narrow your field of vision. When I need to step outside that bubble, I go 233 miles south to Rocky Mount, North Carolina. Time there reconnects the policy debates and conversations on globalization, deindustrialization, the energy transition, and artificial intelligence to the everyday realities of job growth, economic opportunity, and stable, healthy communities.

Birthplace of Thelonious Monk, Walter “Buck” Leonard, generations of the Edwards, Rocky Mount has the key ingredients that define small-town North Carolina: genuine friendliness, an unhurried pace, and outstanding barbecue. Rocky Mount sits in North Carolina’s Twin Counties - Nash and Edgecombe - divided down the middle by the railroad, with one half of the city in each. Stepping off the train in downtown Rocky Mount, into a picturesque but nearly empty city center, stirred my curiosity about the area’s past and what it might reveal about the future.

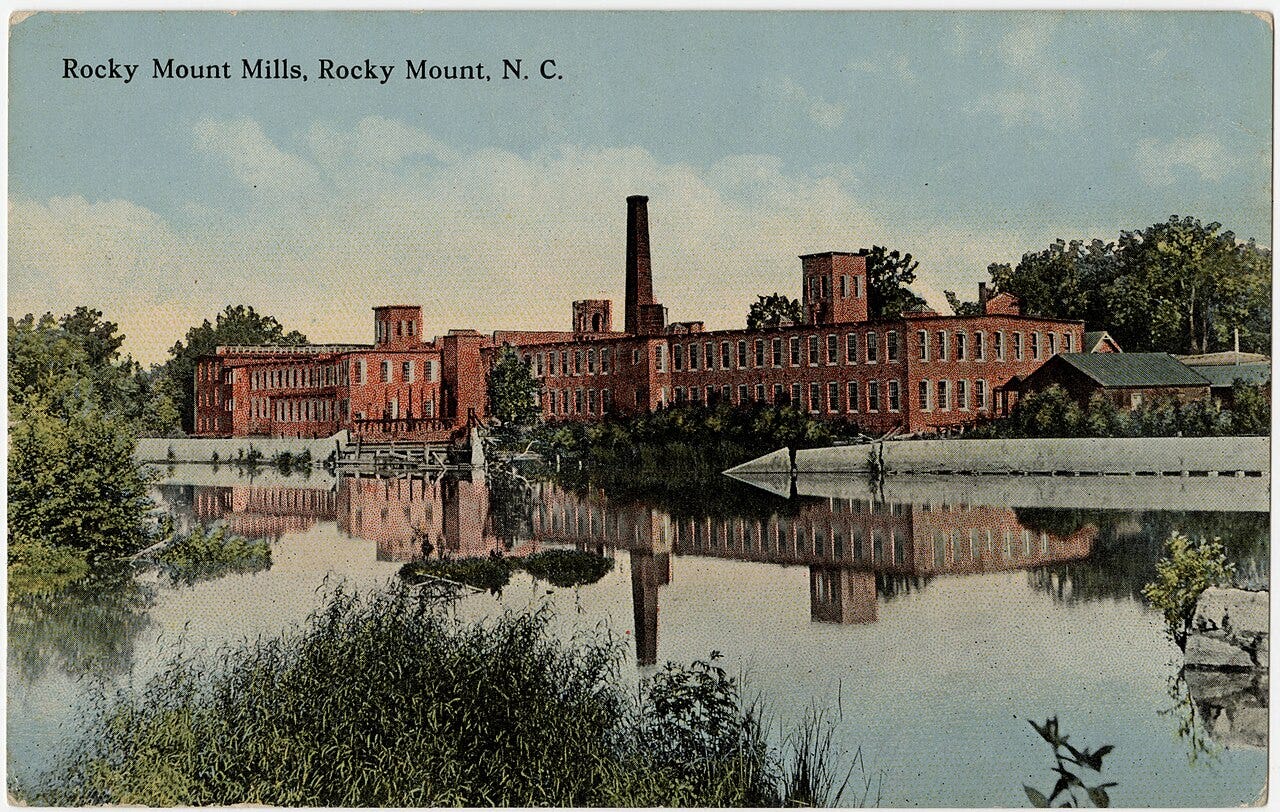

Rocky Mount’s geography set the stage for its rise in the nineteenth-century. The town sits along the fall line in eastern North Carolina, where the Coastal Plain meets the Piedmont. Here, the Tar River’s drop provided reliable water power to support early industrial activity, including one of the state’s first cotton mill, Rocky Mount Mills, in the early 1800s.

The region’s sandy soils were ideal for growing “bright-leaf” tobacco, which was well suited to the booming cigarette market. During the late 19th and 20th centuries, Rocky Mount became a major tobacco market and auction center for Eastern North Carolina, Rocky Mount ranked among the world’s most important bright-leaf tobacco markets, with warehouses that linked local farms to global trade. Farmers sold their tobacco at warehouses to buyers, including export firms like Imperial Tobacco. Imperial Tobacco’s warehouse still dominates downtown, not far from where my great-grandfather worked at the Export Leaf Tobacco Company.

As the first taste of relatively mild weather for travelers going south, Rocky Mount’s location near the midpoint on the rail line (and eventually Interstate 95) between New York and Florida made it a well known stop for winter for “snowbirds” fleeing the northern winter. The Atlantic Coast Line Railroad (ACL) main line ran directly through Rocky Mount, carrying famous deluxe, streamlined passenger trains like The Champion and the Florida Special to connect New York to Florida resorts.

Riding today’s successor to the Florida Special, I think about my grandfather and his father before him - Black men in the Jim Crow South who worked long, demanding hours as laborers and mechanics to keep those trains running smoothly. Their jobs were grueling, yet they offered something precious in that era: steady pay and a measure of security that few other paths provided Southern Black families. That hard-earned stability became the foothold my family needed. It allowed my father and his siblings to become the first generation of Edwards to attend college - a quiet, powerful legacy carried forward on the very rails my grandfather helped maintain.

For most of the 20th century, Rocky Mount was humming. Old photographs show warehouses full of tobacco, streets full of cars, and communities full of people. Outside of the harvest season, the warehouses held “June German” dances. (The “colored” June Germans had appearances Count Basie and Louis Armstrong).

It was an era of abundance, built on an economy and way of life that must have felt as permanent as our own neoliberal era did until a few years ago. But permanence is an illusion. As the 1990s approached, an economy built on mills, tobacco, and the railroad began to unravel, like the seams of a warm, trusty, but aging, coat.

First, globalization and trade liberalization took a heavy toll on North Carolina’s traditional industries, particularly textiles, apparel, and furniture. From the 1990s through the early 2010s, the state lost roughly 400,000 manufacturing jobs as imports surged and factories closed or relocated - trends that began earlier but accelerated with agreements like NAFTA 1994 and China’s WTO entry in 2001. Rocky Mount Mills, a cornerstone of the local economy, shut down in 1996 amid this broader textile downturn, leading to widespread layoffs and further hollowing out the industrial base. Separately, tobacco faced a long, gradual decline that was driven by changing cultural attitudes, mounting public health concerns, and reduced domestic demand. The 1998 Master Settlement Agreement reshaped the cigarette industry by imposing massive payments on manufacturers, while the 2004 Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act immediately ended quotas and price supports starting with the 2005 crop year, delivering a final blow to many small farms. Together, these twin forces left behind empty warehouses, shuttered stores, and communities grappling with profound change.

These economic shocks intersected with and exacerbated structural inequalities. Historical redlining and investment patterns favored white neighborhoods in Nash County, while Black communities in Edgecombe County suffered from chronic underinvestment. Schools, small businesses, and professional services declined, prompting residents and employers to move northward toward suburban areas where new housing and jobs were concentrated. To top it all off, in September 1999, Hurricane Floyd struck eastern North Carolina with relentless fury, unleashing catastrophic flooding that submerged up to 30% of Rocky Mount under murky, rising waters—turning streets into rivers and neighborhoods into lakes. The deluge severely damaged or destroyed thousands of homes and businesses. Many survivors and enterprises, wary of the Tar River’s unpredictability, chose not to rebuild in the vulnerable downtown and low-lying areas. Instead, they relocated to safer, higher-ground suburban sites equipped with modern infrastructure and greater resilience against future storms. This accelerated a cycle of urban flight from the historic core, leaving behind boarded-up storefronts, vacant lots, and echoing silence. A “dying town” narrative cast a long shadow into the early 2000s.

The years following Hurricane Floyd were marked by false starts and unglamorous persistence. Local officials leveraged existing assets - rail and highway connectivity, affordable real estate, proximity to major markets—to attract employers in logistics (Kanban Logistics), advanced manufacturing (Cummins Engine), healthcare (UNC Nash), and clean energy. The 134-megawatt Fern Solar Project, a utility-scale solar farm in Edgecombe County, began operating in late 2020. By 2019, Forbes listed Rocky Mount as one of the best “small places” to do business. Yet progress has been uneven, and downtown’s enormous potential remains largely untapped.

By 2025, momentum has shifted toward data centers as artificial intelligence infrastructure expands. In late 2025, Edgecombe County approved zoning changes to permit data centers, paving the way for a proposed $19.2 billion, 900-megawatt hyperscale campus by Energy Storage Solutions, with groundbreaking anticipated in early 2026. Hyperscalers are drawn to the region for familiar reasons: large tracts of available land, access to power infrastructure, and favorable geography.

Data centers promise capital investment and tax revenue, but - as elsewhere -they also raise questions. Will they generate durable employment and local opportunity? What will their environmental footprint be? Will opportunities flow to those residents who have been left behind? Will these investments help reimagine downtown Rocky Mount as an entrepreneurial hub, or will Rocky Mount once again host infrastructure through which prosperity flows only to some? Rocky Mount and the Twin Counties tell a deeply American story: mill power and tobacco wealth giving way to globalization’s disruptions, followed by painful reinvention.

From fall line to fiber lines, Rocky Mount’s evolution offers crucial perspective. As the U.S. and global economies shift into new, still-undefined forms, places like Rocky Mount reveal what economic transformation actually means for communities and the people who live through it. Whether the region thrives with broadly shared prosperity or merely survives will tell us something important not only about rural America’s future, but also about whether we’ve learned to listen to the places where policy finally touches ground

.